Module 1: Fundamentals of Evidence Based Medicine

INTRODUCTION

A physician describes a 43 year old male patient who experienced an exacerbation of his chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the form of a pneumonia, requiring hospitalization. The patient had never been hospitalized before. The patient had been taking his ipratropium bromide 6 puffs four times a day (qid) regularly. The patient was given prednisone and antibiotics. A physical examination revealed crackles in the left lower base, an X-ray confirmed these findings, and bloodwork showed an increase in white blood cells (WBC) to 12 cells/mcl. The physician is still concerned as the O2 saturation is low.

A physician describes a 43 year old male patient who experienced an exacerbation of his chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the form of a pneumonia, requiring hospitalization. The patient had never been hospitalized before. The patient had been taking his ipratropium bromide 6 puffs four times a day (qid) regularly. The patient was given prednisone and antibiotics. A physical examination revealed crackles in the left lower base, an X-ray confirmed these findings, and bloodwork showed an increase in white blood cells (WBC) to 12 cells/mcl. The physician is still concerned as the O2 saturation is low.

In the past, the physician would rely on experience and peer consensus to inform the patient that the risk of future infections with hospitalizations was high, and that the patient should continue his medication and see his family physician for follow-up*… providing you with very little opportunity to discuss the case any further.

Today, the physician will most likely respond favorably to a citation of a robust clinical trial* with valid, convincing evidence on the role of your agent in managing COPD… providing you with an opportunity to discuss patient management options.

This Module explores the process of evidence-based medicine* (EBM) and how it influences the way practitioners view and manage the uncertainties of clinical medicine; the vast volume of literature; the introduction of new technologies; the concern about rising medical costs; and the quality and outcomes of intervention*.

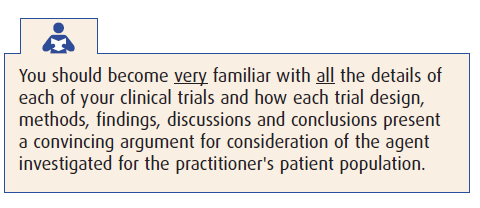

As a pharmaceutical professional, your ability to understand the process and role of Evidence-Based Medicine in the clinical setting will have an impact on how health care practitioners view your role – and the role of your products – in their practice.

MODULE OVERVIEW

…Another Resource

Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) is neither a “cure-all” nor a replacement for traditional clinical process. This module examines the limitations of traditional clinical models, and how the addition of EBM to the practitioner’s toolkit results in enhanced clinical decision-making and patient centric management of medical problems. EBM enables each physician to leverage the synergy of clinical research and expertise, and patient-centric decision-making in order to improve clinical outcomes.

The five steps in the process of EBM will be examined in some detail. This includes how physicians…

-

-

- construct productive questions based on clinical needs

- research the answers using evidence-based techniques

- evaluate the validity* and clinical importance of findings

- determine when evidence merits introduction into clinical practice, and

- evaluate clinical outcomes where EBM has been applied.

-

The Module also explores how to leverage EBM results in future discussions with healthcare practitioners (HCPs). Understanding the EBM process will not only help you appreciate how a prescriber may view the approved reprints you carry, but also how to position them more effectively in the clinical process.

This last issue – EBM and healthcare practitioners looks at regulatory requirements in the application of EBM in clinical practice, the role of EBM in interactions between pharmaceutical representatives and prescribers… and a few challenges associated with the adoption of evidence-based medicine in clinical practice.

MODULE GOAL:

The overall goal of this Module is to ensure that you have a solid understanding of what evidence-based medicine is and how it works. This Module explores the role EBM plays in clinical practice –  and most important – interactions between pharmaceutical professionals and health care practitioners.

and most important – interactions between pharmaceutical professionals and health care practitioners.

Module Objectives….

Upon completion of this module, you will be able to:

-

-

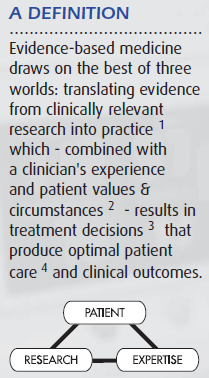

- Describe the currently accepted definition of evidence-based medicine

- Describe the advantages and limitations of EBM in current clinical practice

- List the 3 components of EBM, and how relevant research combined with a physician’s clinical expertise and a patient-centric approach can result in improved outcomes

- List the 5 steps in the EBM process and how each contributes to improved clinical outcomes for patients

- Position the role of EBM in regulatory affairs, treatment strategies, and interactions between pharmaceutical professionals and HCPs

- Cite several reputable resources for additional information on evidence based medicine

- Evaluate your recall and understanding of the Module’s content

-

WHAT IS EVIDENCE-BASED MEDICINE?

Evidence-Based Medicine is…

“…an emphasis on the examination of evidence from clinical research for clinical decision-making instead of unsystematic clinical experience, and pathophysiologic rationale.”

“…an emphasis on the examination of evidence from clinical research for clinical decision-making instead of unsystematic clinical experience, and pathophysiologic rationale.”

Center for Health Evidence

“…integration of clinical expertise, patient values, and the best evidence into the decision making process for patient care.”

(Sackett D, 1996)

“…an approach to practicing medicine in which the clinician is aware of the evidence in support of clinical practice, and the strength of that evidence.”

Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group

“…the tools you need to find important new medical research quickly and easily, and to work out its implications for your practice.”

SUNY Downstate Medical Center

“…the abstract exercise of reading and appraising the literature into the pragmatic process of using the literature to benefit individual patients while simultaneously expanding the clinician’s knowledge base.”

Bordley DR, 1997

SOUND, RELEVANT RESEARCH

The foundation of evidence-based medicine is clinical investigation that typically explores a health care issue in one of several categories:

Your general discussions with a health care practitioner may touch upon issues related to all these types of research, but in general you will find yourself focusing on treatment… specifically intervention with pharmaceutical products. Most approved reprints carried by pharmaceutical sales professionals are from this category.

CLINICAL EXPERTISE

Based on years of training through medical school, clerkship, residency and independent clinical practice, a HCP brings extensive experience to bear on each step of patient evaluation and management.

Based on years of training through medical school, clerkship, residency and independent clinical practice, a HCP brings extensive experience to bear on each step of patient evaluation and management.

As will be discussed later, a prescriber’s clinical expertise compliments evidence-based medicine. Therefore a perceptive pharmaceutical professional will employ careful listening skills to understand how practitioners use their vast clinical expertise to assess, diagnose, and treat each case. Doing so will reveal specific opportunities for discussing physicians’ beliefs or preferred methods that are also supported by the methods or evidence in the clinical trials behind your product.

In the context of evidencebased medicine, HCPs integrate the sum of their intrinsic clinical expertise with the best, valid extrinsic clinical evidence to optimize individual patient care.

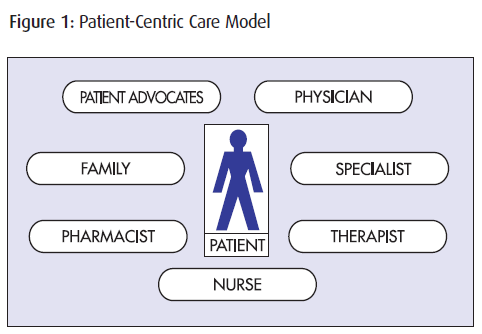

PATIENT NEEDS

Because of the unique values and circumstances of each patient, the patient has long been the focus of most care models. Effective patient management starts with patients and the information collected from them using assessment tools and activities… continues with the patient as clinical expertise and treatment decisions strive for improved patient outcomes… and ends with patients as their progress is followed and evaluated, and their treatment adjusted accordingly.

SECTION SELF-CHECKS

Each Section Self-Check is an opportunity for you to check your recall and comprehension of the topics discussed.

For each question

-

-

- Write in the appropriate information

- Check your answers with the answer key at the back of the Module

- Return to the Section and Topic for a more detailed review

- Advance to the next question

-

The results of the Section Self-Check questions are for your benefit only.

SECTION SELF-CHECK

Q1:

List the 3 key components of evidence-based medicine.

SELF-CHECK RESULTS

Q1:

List the 3 key components of evidence-based medicine.

1. Sound, relevant research

2. Physician’s clinical expertise

3. Patient needs

R: Section 2: What is (1.2)

THE CASE FOR EBM

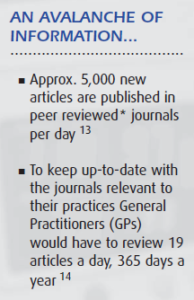

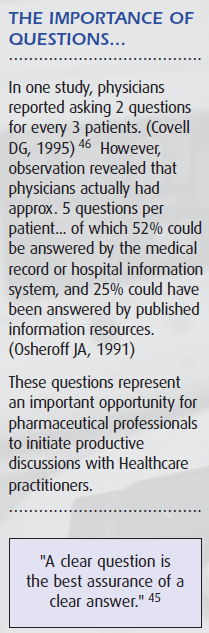

HCPs face constant change in medical technology and patient management… with increased pressure to reduce healthcare costs while improving the quality of patient care and outcomes. With increased patient loads and less time for reading and research, physicians must rely more on standards of practice and treatment algorithms recommended by key opinion leaders.

Given the challenging environment in which physicians must practice, the use of medical literature to guide medical practice increases the opportunity for the adoption and application of evidence-based medicine. However, as with any clinical tool, pharmaceutical professionals must be familiar with the pros and cons of evidence-based medicine in order to ensure fair balance in discussion.

This Section explores 3 factors that must be taken into consideration when discussing or applying evidence-based medicine

-

-

- Shortcomings of traditional clinical resources and process

- Advantages of EBM in clinical practice

- Limitations of EBM

-

SHORTCOMINGS OF TRADITIONAL CLINICAL RESOURCES AND PROCESS

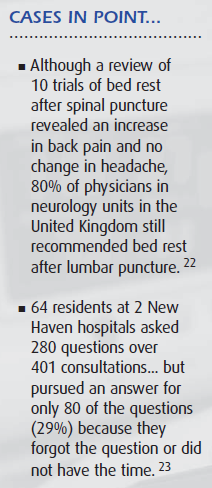

Long recognized as the mainstay of clinical practice… expert opinion and standards of practice are not always effective in applying scientific information to clinical issues – often because opinion and practice are based on unsystematic observations from clinical experience; are subject to variation; or are not current or consistent with the latest evidence. In fact, there is a statistically and clinically significant negative correlation between the knowledge of up-to-date care and the time that elapses after physicians graduate from medical school.

This deterioration in the currency of clinical knowledge has traditionally been addressed by continuing medical education (CME). However trials have demonstrated that CME often fails to modify clinical behavior and performance, proving to be ineffective in improving patient outcomes.

And when trying to keep current on their own, clinicians are faced with a shortage of time, out-of-date textbooks, and disorganized clinical journals. Clearly there is an opportunity to change how medical literature is used in guiding the clinical decision making process.

ADVANTAGES OF EBM IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

It is clear that clinicians need better tools to efficiently evaluate medical literature for more effective use in their practice, and that those who keep up-to-date practice better medicine.

Given that case-based CME has better success in improving clinical behavior, and that a problem-based approach assists physicians in keeping current with clinical research, the fundamentals of EBM are already in place and in practice. Physicians who search literature based on patient needs, then evaluate and apply the best of the results, are in effect already practicing evidence-based medicine.

Today, almost every drug, surgical therapy and diagnostic test must demonstrate efficacy in clinical trials before entering clinical practice. Articles on how to access, evaluate, and interpret this medical literature are prevalent; issues of trial methods & design and the criteria used to evaluate the validity of evidence are emphasized more in textbooks and article abstracts; and practice guidelines are more frequently based on rigorous reviews of evidence.

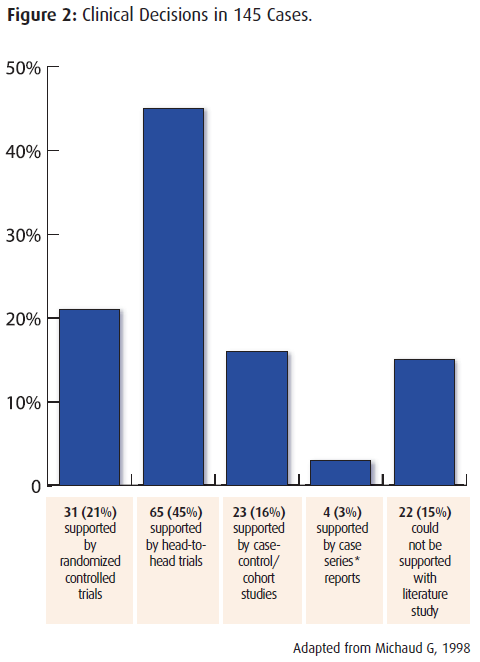

“Most primary therapeutic clinical decisions in 3 general medicine services are supported by evidence from randomized controlled trials*.”

In the analysis of 145 cases and their clinical decisions:

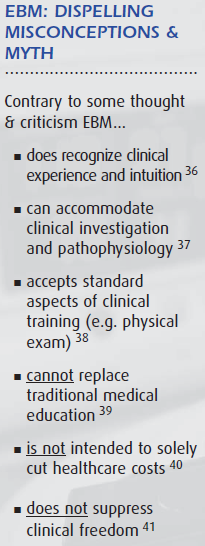

LIMITATIONS OF EBM

External clinical evidence can never replace the physician’s clinical expertise that decides whether or not evidence is appropriate for a patient, and if it is, how it should be applied.

And while an evidence-based intervention may improve patient care and outcomes, it may not always be the lowest cost solution.

Evidence from literature is not always definitive… results may be valid, might demonstrate efficacy, and can improve outcomes. And aside from results from process studies and outcomes research, there is no evidence from randomized controlled trials that EBM has a positive impact on clinical outcomes.

And finally, despite a strong argument for EBM, changing the behavior of all stakeholders in health care – including that of patients – is a challenging task… questioning how much evidence-based medicine is being applied in daily patient care.

SECTION SELF-CHECK

Q1:

List several problems found in traditional clinical resources and processes that rely on expert opinion and standards of practice.

Q2:

List several limitations of evidence-based medicine.

SELF-CHECK RESULTS

Q1:

List several problems found in traditional clinical resources and processes that rely on expert opinion and standards of practice.

1. Often based on unsystematic observations from clinical experience

2. Subject to variation

3. Not always current or consistent with latest evidence

4. Clinicians have insufficient time

5. Current resources such as textbooks are out-of-date

R. Section 3. Topic 1: Shortcomings of traditional clinical resources and process (1.3.1)

Q2:

List several limitations of evidence-based medicine.

1. Not always the lowest cost solution

2. Evidence from literature is not always definitive

3. No evidence from randomized, controlled trials of positive impact on clinical outcomes

4. Requires a change in behavior of all stakeholders (physicians, healthcare team, administration, patients)

R. Section 3. Topic 3: Limitations of EBM (1.3.3)

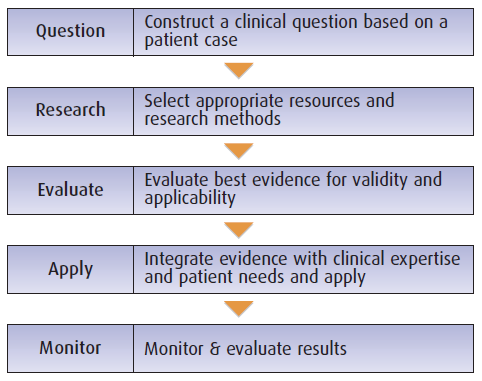

THE FIVE STEPS IN EBM

“The process of applying evidence-based medicine to clinical situations begins and ends with the patient.

First, a specific patient management issue is clearly defined and framed in the form of a question; next, search strategies are used to obtain the best available evidence; then the quality of the evidence from relevant articles that address the therapeutic issue and patient is evaluated… including the risk/cost/benefit of the intervention to the patient; then the intervention is applied, monitored, and adjusted accordingly.”

This Section explores the 5 steps that are the foundation of the evidence-based medicine process

1. Phrasing questions

2. Researching answers

3. Evaluating the evidence

4. Integrating and applying evidence

5. Monitoring and evaluating results

Example:

The following patient case study will be used to demonstrate the 5 steps of evidence-based medicine.

Patient Profile:

Patient Profile:

Jasmine is 13 years old and has a history of asthma ever since she was a child. Her asthma is exacerbated by allergens including cats and dogs, by smokers and by exercise.

She had been hospitalized once 3 years ago for a severe asthma attack. Since that attack her previous family doctor had put her on very high doses of steroids to manage her asthma. At the present time her asthma remains very stable. She is extremely diligent about taking her medications (fluticasone and salbutamol) and wants desperately to stay out of the hospital. Her mother and her 2 sisters have lived in this town ever since their parent’s divorce 6 years ago. Her mother is concerned about Jasmine using steroids.

You mention to the mother that Jasmine could take montelukast but you are not certain if this will help reduce her need for steroids. You decide to research this question before her next visit.

STEP ONE: PHRASING QUESTIONS

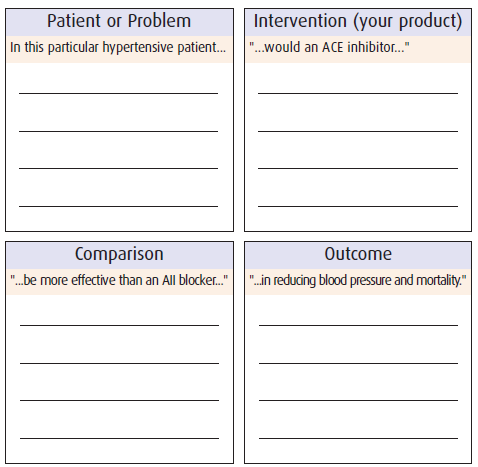

A clinical question considers four elements known by the acronym PICO:

A clinical question considers four elements known by the acronym PICO:

P the Patient

I the Intervention or exposure

C a Comparison (of the intervention) with an alternative

O an Outcome

A PICO question always begins and ends with the patient or a clinical outcome. For example: “In this particular hypertensive patient, would an ACE inhibitor be more effective than an AII blocker in reducing blood pressure and mortality?”

The patient: A well constructed, patient-centric clinical question improves the success of finding relevant and effective evidence for patient management. An understanding of the issues related to specific patient problems leads to a well-formed clinical question that can help efficiently target the search for evidence. A product’s indication often specifies a patient type (eg, “In this particular hypertensive patient…”)

Intervention/exposure can implicate therapeutic, preventive, or diagnostic intervention. The type of ‘questions’ of interest to pharmaceutical professionals address possible outcomes from therapeutic pharmaceutical intervention (eg, “…would an ACE inhibitor…”).

Comparison between the intervention/exposure and an alternative may not always be possible or necessary. In the case of drug therapy, it typically involves comparison with placebo*, or an agent from the same or another therapeutic class (eg, “…be more effective than an AII blocker…”)

Outcomes reflect the preferred clinical end-points that a physician aims to achieve from an intervention or exposure. A product’s indication often specifies a desired outcome (eg, “…in reducing blood pressure and mortality.”)

Example

Clinical Question:

In patients with asthma, is montelukast effective in reducing the need for inhaled steroids?

It is a therapy question and the best evidence would be a randomized controlled trial (RCT). If we found numerous RCTs, then we might want to look for a systematic review*.

Exercise

With one or more product(s) that you are currently promoting, use the table below to construct a clinical question that you would like the opportunity to discuss with a prescriber.

Note that your product can become the ‘comparison’ product when managing objections.

STEP TWO: RESEARCHING ANSWERS

Once a clinical question has been constructed it has to be researched – most often using on-line bibliographic, source, textual or factual medical databases. The most efficient method of finding relevant information is with a search strategy – by fragmenting the clinical question into key search words, adding Boolean operators (AND/OR/NOT), and by narrowing a search with filters.

It is not within the scope of this program to discuss search methods and strategies. Good resources on the subject can be found at:

Center for Evidence-based Medicine: www.cebm.net/searching.asp

Health Sciences Library, UNC-Chapel Hill

National Library of Medicine PubMed tutorial: www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/pubmed_tutorial/m1001.html

National Center for Biotechnology Information MeSH database tutorial: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=mesh

The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, SUMSearch

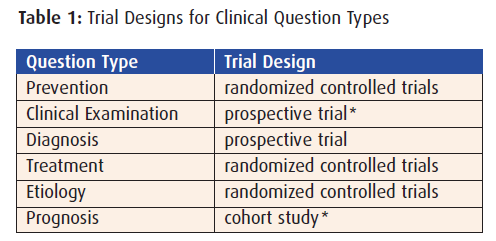

Regardless of the methods or mechanisms used to search for evidence in response to clinical questions, the type of question often determines the trial category most likely to provide the required evidence.

Regardless of the methods or mechanisms used to search for evidence in response to clinical questions, the type of question often determines the trial category most likely to provide the required evidence.

For clinical questions regarding therapy, the best study design to search for is a randomized controlled clinical trial… the same type used to obtain an indication for a drug, and that pharmaceutical professionals are often authorized to carry. These trials typically compare the agent with a placebo (placebo controlled) or to another inor out-of-class agent (head-to-head).

Types of trials will be discussed in greater detail in Module 3: Clinical Trial Design.

Example

Researching Answers:

Our clinical question: “In patients with asthma, is montelukast effective in reducing the need for steroids?” is a therapy question for which the best evidence would be found in a randomized controlled trial (RCT). If numerous RCTs were found, then a systematic review may be a more efficient alternative.

BMJ. 1999 July 10; 319(7202): 87-90. Copyright © 1999, British Medical Journal

Randomised, placebo controlled trial* of effect of a leukotriene receptor antagonist, montelukast, on tapering inhaled corticosteroids in asthmatic patients

Objective

To determine the ability of montelukast, a leukotriene receptor antagonist, to allow tapering of inhaled corticosteroids in clinically stable asthmatic patients.

Design

Double blind, randomised, placebo controlled, parallel group study. After a single blind* placebo run in period, during which (at most) two inhaled corticosteroids dose decreases occurred, qualifying, clinically stable patients were allocated randomly to receive montelukast (10 mg tablet) or matching placebo once daily at bedtime for up to 12 weeks.

Setting/Participants

-

-

- 23 academic asthma centres in United States, Canada, and Europe.

- 226 clinically stable patients with chronic asthma receiving high doses of inhaled corticosteroids (113 randomised to montelukast and 113 to placebo).

-

Interventions

-

-

- 2 weeks, the inhaled corticosteroids dose was tapered, maintained, or increased (rescue) based on a standardized clinical score.

- Main outcome measures

- Last tolerated dose of inhaled corticosteroids.

-

Results

Compared with placebo, montelukast allowed significant (P=0.046) reduction in the inhaled corticosteroid dose (montelukast 47% vs placebo 30%; least square mean* difference 17.6%, 95% confidence interval* 0.3 to 34.8). Fewer patients on montelukast [18 (16%) vs. 34 (30%) placebo, p=0.01] required discontinuation because of failed rescue.

Conclusions

Montelukast reduces the need for inhaled corticosteroids among patients requiring moderate to high doses of corticosteroid to maintain asthma control.

Key Messages

-

-

- Leukotriene receptor antagonists have complementary action to inhaled corticosteroids in asthma

- Many patients receive higher doses of inhaled corticosteroids than clinically required

- In this placebo controlled trial, montelukast allowed significant reduction of inhaled corticosteroid doses

- Fewer patients receiving montelukast had failed rescue versus patients receiving placebo

-

Exercise: Research the competitive field

Exercise: Research the competitive field

Put yourself in the position of a physician who is conducting a literature search for evidence on the best pharmaceutical intervention for patients and conditions for which your product(s) is/are indicated.

Make note of current articles reporting on agents other than yours that the search reveals. Although you may not be authorized to discuss these studies, you should be familiar with the information in the abstracts.

STEP THREE: EVALUATING EVIDENCE

Variation in patient populations, research methods and interpretation of results suggest that articles, reviews or trials are not all created equal. Health care practitioners require a standardized procedure they can use to determine the validity of the evidence they collect.

In general, this involves answering several categories of questions:

1. Are the results valid and/or accurate?

1. Are the results valid and/or accurate?

-

-

- Was the trial designed and conducted according to rigorous protocols* and procedures?

- Were the results collected and summarized appropriately?

- Are the results an unbiased estimate of the treatment effect?

- Were all important outcomes included?

-

2. What exactly are the results, and are they important?

-

-

- How strong is the evidence (size and precision of investigation)?

- Are the results consistent (if not, why not)?

- Are they believable (could uncertainty change the results)?

- Does the intervention result in a clinically important benefit for patients?

-

3. Do the results apply to the patient and can they benefit him/her?

-

-

- Is the benefit vs. risk appropriate for the patient?

- What impact will the treatment have on the patient?

- Is the trial population similar to the patient in question?

-

How to interpret and evaluate trial results is discussed in greater detail in Module 4: Anatomy of a Peer Reviewed Article and Module 5: Interpreting Clinical Results.

Example:

Evaluating the Evidence:

In the article selected to best answer the clinical question for Jasmine:

-

-

- patients were randomly assigned to receive montelukast or placebo

- patient characteristics were evenly distributed within the two groups

- all patients who entered the trial were properly accounted for at its conclusion with complete follow-up.

- analysis was done by intention to treat*

- researchers and data analysts were blinded* to the treatment groups

- characteristics were evenly distributed within the 2 groups

- both groups were treated equally

- montelukast did reduce the need for steroids predominantly in patients who were taking higher than necessary steroids

-

STEP FOUR: INTEGRATING AND APPLYING EVIDENCE

STEP FOUR: INTEGRATING AND APPLYING EVIDENCE

Recall that evidence-based medicine is based on three factors:

-

-

- Sound, relevant research

- Clinical expertise

- Patient focus

-

Once the evidence has been collected and validated, practitioners use their clinical expertise to make a clinical decision based on the original clinical question… taking into consideration the patients’ individual preferences, values, and situations.

As discussed earlier, EBM begins and ends with the patient. In this step, HCPs carefully consider several issues:

-

-

- Biological (differences in drug metabolism, immune responses, environmental factors, patient disease profile vs. that of trial population)

- Socioeconomic (compliance problems, formulary availability, etc.)

- Epidemiologic (co morbidities*/adverse events that affect outcome)

-

Example:

Applying the Evidence:

The study population appears to be similar enough to Jasmine that we can consider the results as applicable to her case.

The results of this study indicate that montelukast can reduce her need for high steroid doses. In fact, it would appear that montelukast may be an appropriate therapy to help keep Jasmine’s asthma stable while reducing her need for high doses of steroids.

STEP FIVE: MONITORING AND EVALUATING RESULTS

Applying the knowledge gained from well researched, convincing evidence to a clinical scenario does not always guarantee success. Some health care practitioners may not be comfortable in immediately applying evidence-based medicine to patients… especially if it is not in line with long-held expert opinion, standards of practice or institutional policy.

Also, the practitioner’s clinical expertise in monitoring and evaluating patient progress may determine that an evidencebased clinical decision is not producing optimal results for a particular patient… requiring a modification to the treatment or change to the therapeutic course.

Example:

Integrating Results:

If Jasmine elects to be treated with montelukast, there will be a need to monitor therapy, lower the dose of steroids, and watch for exacerbations of her asthma. Her mother is willing to pay close attention to her asthma while her dose of inhaled steroids is dropped, as well as giving her her daily dose of montelukast. Jasmine’s mother is extremely pleased with the medication her physician suggested so that the dose of steroids can probably be lowered.

SECTION SELF-CHECK

Q1:

List the 5 steps in the evidence-based medicine process.

Q2:

List the 4 components of well constructed clinical questions.

Q3:

List at least 5 types of clinical questions that determine the category of trial that should be researched.

Q4:

List at least 5 questions that should be answered in order to determine the validity of clinical evidence.

Q5:

List several patient issues that a physician must consider when integrating evidence into patient management.

Q6:

List 3 reasons why a healthcare practitioner may elect not to apply evidence that he/she has researched to the management of a patient.

SELF-CHECK RESULTS

Q1:

List the 5 steps in the evidence-based medicine process.

1. Construct/phrase clinical question

2. Research answer

3. Evaluate evidence

4. Integrate and apply evidence

5. Monitor and evaluate results

R: Section 4: The 5 Steps in EBM (1.4)

Q2:

List the 4 components of well constructed clinical questions.

1. The patient

2. Intervention or exposure

3. Comparison of the intervention with an alternative

4. Desired outcomes

R: Section 4. Topic 1: Step One: Phrasing questions (1.4.1)

Q3:

List at least 5 types of clinical questions that determine the category of trial that should be researched.

1. Prevention

2. Clinical examination

3. Diagnosis

4. Therapy

5. Etiology

6. Prognosis

R: Section 4. Topic 2: Step Two: Researching answers (1.4.2)

Q4:

List at least 5 questions that should be answered in order to determine the validity of clinical evidence.

1. How strong is the size and precision of the evidence?

2. Are the results consistent?

3. Are they believable?

4. Does the intervention result in a clinically important benefit to patients?

5. Was the trial designed/conducted according to rigorous protocols and procedures?

6. Are the results an unbiased estimate of the treatment effect?

7. Were all important outcomes included?

8. Is the benefit vs. risk appropriate for the patient?

9. What impact will the treatment have on the patient?

10. Is the trial population similar to the patient in question?

R: Section 4. Topic 3: Step Three: Evaluating evidence (1.4.3)

Q5:

List several patient issues that a physician must consider when integrating evidence into patient management.

1. Differences in drug metabolism

2. Immune responses

3. Environmental factors

4. Patient disease profile vs. that of the trial population

5. Compliance

6. Formulary availability

7. Co morbidities/adverse events

R: Section 4. Topic 4: Step Four: Integrating & applying evidence (1.4.4)

Q6:

List 3 reasons why a healthcare practitioner may elect not to apply evidence that he/she has researched in the management of a patient.

1. Evidence may not agree with expert opinion or standards

of practice

2. Evidence may not conform to institutional policy

3. Application of evidence is not producing optimal results

R: Section 4. Topic 5: Step Five: Monitoring and evaluating results (1.4.5)

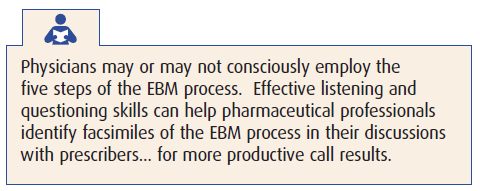

EBM IN THE HEALTH CARE PRACTITIONER’S OFFICE

The advantage of applying proven, valid clinical evidence in disease prevention and the clinical examination, diagnosis, treatment, etiology and prognosis of patient management makes a good case for evidence-based medicine. However, not all physicians may understand or adopt and practice EBM to its full potential.

This places the responsibility on the pharmaceutical professional to identify when and how EBM should best be introduced into discussion with HCPs. At the same time, you must be sensitive to other prevailing conditions that mediate the introduction and discussion of EBM in sales call situations.

This Section explores issues to take into consideration when discussing evidence-based medicine with health care practitioners in the clinical setting:

-

-

- Regulatory implications of EBM

- Challenges of EBM in clinical practice

- Interactions with pharmaceutical professionals

-

REGULATORY IMPLICATIONS OF EBM

Most pharmaceutical professionals are only permitted to discuss clinical issues within the boundaries of the product monograph for the patient types and disease states (and other conditions) for which the product has been indicated.

Other than the product monograph and patient information, professionals must limit discussion regarding articles in peer-reviewed journals to the specific approved reprints they are authorized to carry and distribute.

As a result of the process of practicing evidence-based medicine, HCPs may lead a discussion into two sensitive areas:

-

-

- Off-label use* of a pharmaceutical product

- Clinical articles that professionals are not authorized to discuss

-

It is important to be able to respond appropriately to statements and questions in order to keep a discussion moving toward a successful conclusion… while remaining within legal and regulatory guidelines. In most cases this involves referring the physician to an approved resource such as a fax database that addresses the issue in greater detail, or a clinical specialist who is authorized to discuss off-label use or unapproved clinical articles.

CHALLENGES OF EBM IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

Physicians face many challenges in managing information in order to meet patient needs. Some clinicians are unaware of the available information technology or do not have access to information retrieval systems… especially during clinician-patient encounters.

Physicians face many challenges in managing information in order to meet patient needs. Some clinicians are unaware of the available information technology or do not have access to information retrieval systems… especially during clinician-patient encounters.

Others may be unfamiliar with the question-researchappraise-apply-evaluate process behind evidence-based medicine… or simply do not have the time to integrate it into their practice.

In addition, regulatory, administrative and/or economic constraints associated with the health care system sometimes present counter-productive incentives or barriers to the integration of sound evidence into clinical decisions.

INTERACTIONS WITH HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS

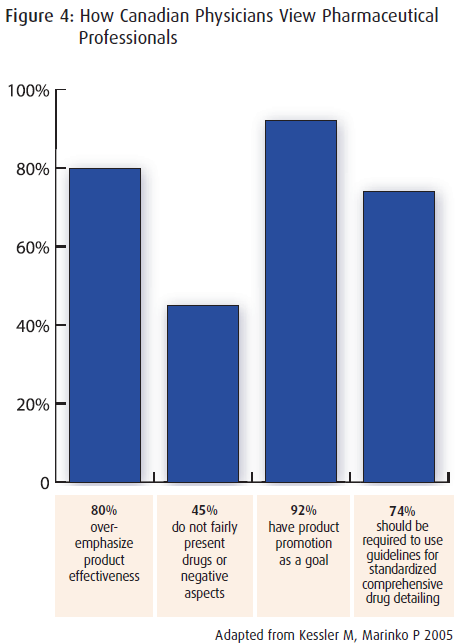

A 1996 survey revealed dissatisfaction among Canadian Physicians about the quality of information provided by the pharmaceutical industry via pharmaceutical professionals (see sidebar).

A 1996 survey revealed dissatisfaction among Canadian Physicians about the quality of information provided by the pharmaceutical industry via pharmaceutical professionals (see sidebar).

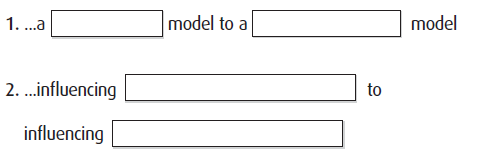

Given the challenges prescribers are facing there is a need for pharmaceutical professionals to move from a sales model to a clinical support model… using evidence-based medicine to assist HCPs in quickly finding relevant, current and effective answers to patient management issues.

Pharmaceutical professionals can leverage EBM by shifting the focus from influencing prescribing habits to influencing clinical behavior… by understanding where to get involved in what Kessler & Marinko call “The MD mind-set” used to make clinical decisions.

-

-

- Identification (of clinical issue)

- Discovery (of clinical evidence)

- Evaluation (of the evidence)

- Action (coming to a clinical decision)

-

HCPs will be more open to the role pharmaceutical professionals can play in their practice if clinical support information is presented with ‘fair balance’ that recognizes any possible biases or shortcomings… therefore improving the validity of the evidence and the credibility of the person presenting it.

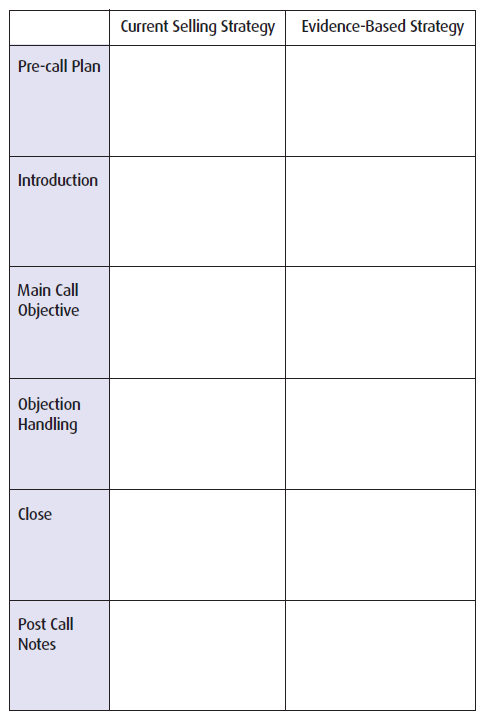

EXERCISE: A SHIFT IN CALL STRATEGY

Recognizing that there are new opportunities in influencing clinical behavior, use the following table to identify how you can use an evidence-based strategy in your next call.

SECTION SELF-CHECK

Q1:

List 2 situations where evidence-based medicine may not be discussed by a pharmaceutical representative with a physician.

Q2:

List several barriers that hinder healthcare practitioners from applying evidence-based medicine to their daily practice.

Q3:

In order to better serve physicians’ needs, pharmaceutical representatives should consider shifting focus from…

SELF-CHECK RESULTS

Q1:

List 2 situations where evidence-based medicine may not be discussed by a pharmaceutical professional with a physician.

1. Evidence suggests off-label use of pharmaceutical product

2. Evidence comes from unapproved clinical article

R: Section 5. Topic 1: Regulatory implications of EBM (1.5.1)

Q2:

List several barriers that hinder health care practitioners from applying evidence-based medicine to their daily practice.

1. Unaware of evidence-based medicine process

2. Unaware of available information technology

3. No access to information retrieval systems

4. Information retrieval systems not on-hand in office/clinic

5. Regulatory, administrative, and/or economic constraints

6. Insufficient time

R: Section 5. Topic 2: Challenges of EBM in clinical practice (1.5.2)

Q3:

In order to better serve physicians’ needs, pharmaceutical professionals should consider shifting focus from…

1. …a sales model to a clinical support model

2. … influencing prescribing habits to influencing clinical behavior

R: Section 5. Topic 3: Interactions with pharmaceutical professionals (1.5.3)

MODULE SUMMARY, REFERENCES & LINKS

This module has addressed the following issues relating to the fundamentals of evidence-based medicine:

Evidence-based medicine integrates three key components:

-

-

- clinically relevant research

- clinical expertise

- patient needs

-

The arguments for EBM are:

-

-

- limitations of traditional clinical resources and process

- advantages of evidence-based problem solving

- most limitations of EBM can be managed

-

The process of evidence-based medicine involves:

-

-

- phrasing clinical questions based on patient needs

- researching evidence-based answers

- evaluating and validating evidence

- integrating and applying evidence to clinical practice

- monitoring patients to evaluate and improve results

-

There are numerous considerations for EBM in a practitioner’s office:

-

-

- conflicts and limitations due to regulatory restrictions

- challenges that HCPs face in adopting and applying EBM

- the role of pharmaceutical professionals in EBM

-

EVIDENCE-BASED MEDICINE RESOURCES

General

Introduction to EBM

Canadian Centres for Health Evidence

Clinical Evidence.org www.clinicalevidence.org

Duke University Medical Center Library

McMaster University, Health Information Research Unit (HIRU)

Mount Sinai Hospital, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine

JAMA “Users’ Guides to Evidence-Based Practice”

School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR) at University of Sheffield

Healthweb.org: Section on Evidence-Based Medicine

University of Rochester, Miner Library

University of York NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/

Guidelines on treatment, diagnosis, and/or prevention

Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ)

Center for Disease Control (CDC) Prevention Guidelines Database

Clinical Practice Guidelines* – Ottawa General Hospital

Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, Second Edition, 1995

Healthy People 2000

Healthy People 2010 www.health.gov/healthypeople

HSTAT – Health Services / Technology Assessment Text

MedWeb – Preventive Medicine

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP) Home Page

National Guideline Clearinghouse www.guidelines.gov/

National Institutes of Health (NIH)–Health Information Index health.nih.gov/

NIH Consensus Development Program Home Page

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) Home Page

Primary Care Clinical Practice Guidelines

Shape Up America

Virtual Hospital www.vh.org/Providers/ClinGuide/CGType.html

Literature Search

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PubMed/

www.hsl.unc.edu

www.cochranelibrary.com

MODULE RESOURCES

- Oxman AD et al. Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature – 1. How to Get Started Jama November 3 1993-Vol270. No. 17 p 2093

- Straus SE. Introduction to Teaching Evidence Based Health Care [Introduction to teaching ebm.ppt] http://www.cebm.net/downloads.asp

- Warner KC. Of course your study says that your company sponsored it! How evidence-based medician can overcome this objection. Pharmaceutical Representative March 2005 p28/29

- Oxman AD et al. Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature – 1. How to Get Started Jama November 3 1993-Vol 270. No. 17 p 2093

- http://denison.uchsc.edu/sg/index.html

- http://www.cebm.net/ebm_is_isnt.asp

- Straus SE. Introduction to Teaching Evidence Based Health Care [Introduction to teaching ebm.ppt] http://www.cebm.net/downloads.asp

- Guyatt, GH, Sackett D, Cook, DJ. Evidence-Based Medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA Nov 4 1992;268(17):2420-5

- Oxman AD et al. Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature – 1. How to Get Started Jama November 3 1993-Vol270. No. 17 p 2093

- Oxman AD et al. Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature – 1. How to Get Started Jama November 3 1993-Vol270. No. 17 p 2093

- Guyatt, GH, Sackett D, Cook, DJ. Evidence-Based Medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA Nov 4 1992;268(17):2420-5

- Guyatt, GH, Sackett D, Cook, DJ. Evidence-Based Medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA Nov 4 1992;268(17):2420-5

- Glasziou P. Introduction to EBM, July 2003 [intro_to_ebm_2003_glasziou.ppt] http://www.cebm.net/downloads.asp

- Davidoff F, Haynes B, Sackett D, Smith R: Evidence based medicine: a new journalto help doctors identify the information they need. BMJ 1995;310:1085-6.

- Guyatt, GH, Sackett D, Cook, DJ. Evidence-Based Medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA Nov 4 1992;268(17):2420-5

- Oxman AD et al. Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature – 1. How to Get Started Jama November 3 1993-Vol270. No. 17 p 2093

- Ramsey PG, Carline JD, Inui TS et al: Changes over time in the knowledgebase of practicing internists. JAMA 1991;266:1103-7. +

- Evans CE, Haynes RB, Birkett NJ et al: Does a mailed continuing education program improve clinician performance? Results of a randomised trial in antihypertensive care. JAMA 1986:255:501-4

- Shin JH. Haynes RB. Johnston ME. Effect of problem-based, self-directed undergraduate education on life-long learning. Canadian Medical Association Journal 1993; 148(6):969-76)

- Davis DA, Thompson MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB: Changing physician performance. A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA 1995;274:700-5

- Davidoff F, Haynes B, Sackett D, Smith R: Evidence based medicine: a new journal to help doctors identify the information they need. BMJ 1995;310:1085-6.

- Serpell MG et al. Prevention of headache after lumbar puncture: questionnaire survey of neurologists and neurosurgeons in United Kingdom: BMJ 1998;316:1709-10

- Green ML, Ciampi M, Ellis PJ. Residents’ medical information needs in clinic: are they being met? Am J Med. 2000;109:218-2000

- Oxman AD et al. Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature – 1. How to Get Started Jama November 3 1993-Vol270. No. 17 p 2093

- http://www.cebm.net/background.asp

- Davis D et al. Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA. 1999 Sep 1;282(9):867-74

- http://www.cebm.net/background.asp

- http://www.cebm.net/ebm_is_isnt.asp

- Guyatt, GH, Sackett D, Cook, DJ. Evidence-Based Medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA Nov 4 1992;268(17):2420-5

- http://www.cebm.net/ebm_is_isnt.asp

- http://www.cebm.net/ebm_is_isnt.asp

- Oxman AD et al. Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature – 1. How to Get Started Jama November 3 1993-Vol270. No. 17 p 2093

- Straus SE. Introduction to Teaching Evidence Based Health Care [Introduction to teaching ebm.ppt] http://www.cebm.net/downloads.asp

- Davis D et al. The case for knowledge translation: shortening the journey from evidence to effect BMJ 2003;327:33-5

- http://www.cebm.net/background.asp

- Guyatt, GH, Sackett D, Cook, DJ. Evidence-Based Medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA Nov 4 1992;268(17):2420-5

- Guyatt, GH, Sackett D, Cook, DJ. Evidence-Based Medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA Nov 4 1992;268(17):2420-5

- Guyatt, GH, Sackett D, Cook, DJ. Evidence-Based Medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA Nov 4 1992;268(17):2420-5

- http://denison.uchsc.edu/sg/index.html

- http://www.cebm.net/ebm_is_isnt.asp

- http://www.cebm.net/ebm_is_isnt.asp

- http://www.cebm.net/focus_quest.asp

- http://www.hsl.unc.edu/services/tutorials/ebm/whatis.htm

- http://denison.uchsc.edu/sg/index.html

- Oxman AD et al. Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature – 1. How to Get Started Jama November 3 1993-Vol270. No. 17 p 2094

- http://www.hsl.unc.edu/services/tutorials/ebm/whatis.htm

- http://www.pubmedcentral.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract&artid=28156

- Dawes MG. Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine [Decision_Analysis.ppt] http://www.cebm.net/downloads.asp

- Newbery D. Critical Appraisal of Systematic Reviews [Systematic_reviews.ppt] http://www.cebm.net/downloads.asp

- Dawes MG. Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine [Decision_Analysis.ppt] http://www.cebm.net/downloads.asp

- Dawes MG. Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine [Decision_Analysis.ppt] http://www.cebm.net/downloads.asp

- Oxman AD et al. Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature – 1. How to Get Started JAMA November 3 1993-Vol270. No. 17 p 2095

- Guyatt GH, Sackett D, Cook DJ: Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature – How to Use an Article About Therapy or Prevention: Are the results of the Study Valid? JAMA. (1993;270(21):2598-2601) and Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature – How to Use an Article About Therapy or Prevention: What Were the Results and Will They Help Me in Caring for My Patients? JAMA (1994;271(1):59-63).

- Dawes MG. Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine [Decision_Analysis.ppt] http://www.cebm.net/downloads.asp

- Oxman AD et al. Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature – 1. How to Get Started Jama November 3 1993-Vol270. No. 17 p 2093

- Oxman AD et al. Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature – 1. How to Get Started Jama November 3 1993-Vol270. No. 17 p 2095

- Jeff Cuffe’s User’s Guide to the Medical Literature. The Ottawa Hospital – Library Services http://www.ogh.on.ca/library/

- Crowley SD et al. A Web-based compendium of clinical questions and medical evidence to educate internal medicine residents. Acad Med. 2003 Mar;78(3):270-4. [abstract at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=12634206&dopt=Citation]

- Davis D et al. The case for knowledge translation: shortening the journey from evidence to effect BMJ 2003;327:33-5

- http://denison.uchsc.edu/sg/index.html

- Glasziou P. Introduction to EBM, July 2003 [intro_to_ebm_2003_glasziou.ppt] http://www.cebm.net/downloads.asp

- Strang D et al: National Survey on the Attitude of Canadian Physicians Toward Drug-Detailing by Pharmaceutical Representatives. Annales CRMCC, Vol 29. No. 8, December 1996

- Kessler M, Marinko P. Think Like a Doctor: Getting into the MD mindset. Pharmaceutical Representative April 2005 p34-35

- Hayward RSA et al: Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature – How to Use Clinical Practice Guidelines: A. Are the recommendations Valid? JAMA. (1995;274(7):570-4) and Wilson MC et al: Users’ Guide to the Medical Literature – How to Use Clinical Practice Guidelines: A. What Are the Recommendations and Will They Help You in Caring for Your Patients? JAMA. (1995;274(20):1630-2).

- Strang D et al: National Survey on the Attitude of Canadian Physicians Toward Drug-Detailing by Pharmaceutical Representatives. Annales CRMCC, Vol 29. No. 8, December 1996

- Kessler M, Marinko P. Think Like a Doctor: Getting into the MD mindset. Pharmaceutical Representative April 2005 p34-35

Figures

Figure 1: Patient-Centric Care Model – page 9

Figure 2: Clinical Decisions in 145 Cases – page 16

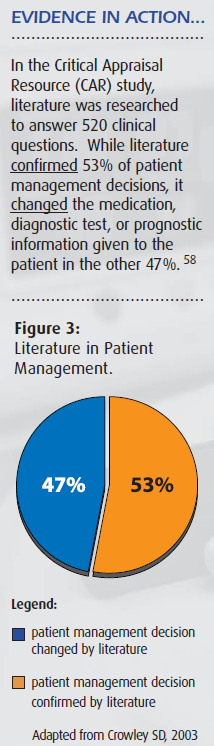

Figure 3: Literature in Patient Management – page 30

Figure 4: How Canadian Physicians View Pharmaceutical Professionals – page 43

Tables

Table 1: Trial Designs for Clinical Question Types – page 24