MODULE 1 – The Constitutional Division of Powers and the Canada Health Act

CHAPTER 1: Federal and Provincial Health Care Responsibilities

In Brief

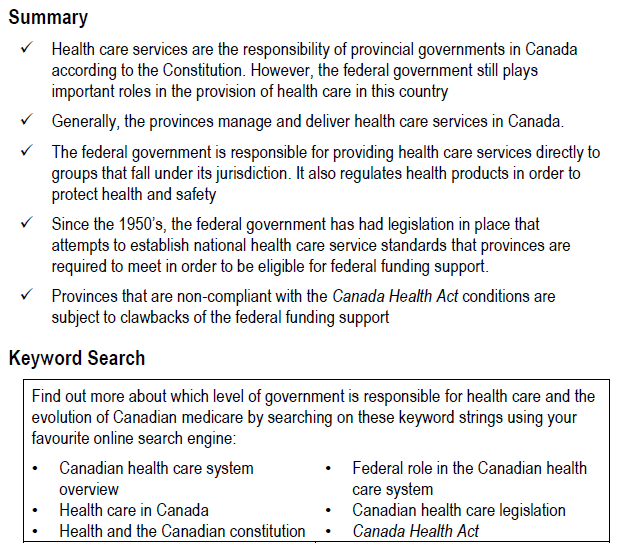

As per the constitutional division of powers in Canada, health care has come to be recognized as an area primarily under provincial jurisdiction. This means that each province runs its own separate health care system and delivers services to the public in the manner that its sees fit. Nationally, all provinces have agreed to support a medicare model, which ensures that all Canadian citizens are able to receive hospital care and physician services without charges.

In an effort to standardize the medicare system nationally, the federal Canada Health Act was passed in 1984 as a means to establish the rules around what minimum standards provinces would have to meet with their public health care plans in order to qualify for federal funding support. Provinces that violate the act’s requirements are subject to reductions in funding.

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- Compare and contrast the respective roles and authorities of the federal and provincial governments with respect to the funding and delivery of health care.

- Describe the evolution of the medicare system nationally.

Federal and Provincial Health Care Responsibilities

While the Canadian Constitution does not explicitly establish which level of government has responsibility for health care, historical precedent and interpretations by the courts have established conclusively that, the provinces have direct constitutional responsibility and authority over the administration and delivery of health care.

The Constitution Act only refers to the operation of hospitals and asylums, identified as a provincial responsibility (with the exception of marine hospitals that explicitly remain a federal responsibility). Beyond that, provincial responsibility for health care delivery derives from their constitutionally assigned powers for regulating property and civil rights and matters of a local or private nature.

Based on the constitutionally-defined responsibility for hospitals and asylums, Canadian courts have consistently deferred responsibility to the provinces for a broad range of health care services including health care insurance regulation, mental health, the distribution of prescription medications, the operation of a range of health care facilities, and the training, licensing and compensation for health care professionals.

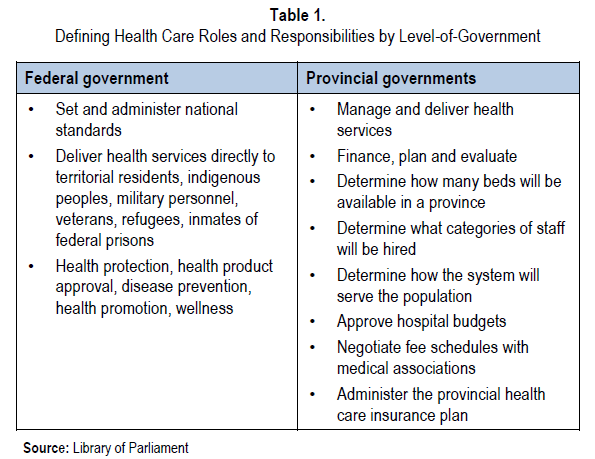

Even so, the federal government retains a number of health-related roles that are associated with its particular constitutional responsibilities. For example, the federal government is responsible for delivering health services directly to groups that fall under its jurisdiction, such as residents of the territories, Canada’s indigenous peoples, members of the Canadian forces, veterans, residents in the process of immigrating to Canada, and inmates in federal penitentiaries. In addition, via its criminal law powers, it takes responsibility for protecting the health and safety of the citizenry through such things as regulating the sale and use of health products, human reproductive materials, cosmetics, tobacco, and other potentially hazardous materials.

Beyond those specific responsibilities, the federal government also relies on its taxation and spending powers to exert authority in the health care arena, primarily by contributing billions of dollars every year to the provinces for the provision of public health care services through the Canada Health Transfer. It also uses the same constitutional provisions to justify its interventions regarding the funding and oversight of heath research activities, health promotion, disease prevention, and control of the dissemination of health information and support for health system reform.

Finally, the federal government has responsibility for a variety of other activities that affect health care, including the environment, regulation of intellectual property protection, workplace safety and occupational health for federal workers, oversight over amateur sport and fitness, and assessments of fitness for duty of pilots and air traffic controllers.

The Evolution of medicare in Canada

Most Canadians think they are covered by a “national” system. However, this is not the case. Canada has never had a national, centrally administered, and uniform health care system.

Instead, Canadians’ public medical benefits are provided through provincially managed and administered health care systems that are distinct to the province in which one lives. The fact that all the provinces offer a relatively similar basket of health benefits to their respective citizenry is due largely to some specific historical developments related to the federal government’s willingness to provide funding support to the provinces for health services.

Starting with the passage of the federal Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act in 1957, this new legislation committed the federal government to provide 50% of the costs of providing hospital services within any province that was prepared to offer publicly funded hospital care to its residents. By 1961, every province in Canada had established its own provincial hospital care program and had negotiated successfully with the federal government for access to the funding support being offered.

In 1966, the federal government expanded the available funding support to all services provided by a physician, whether in hospital or in the community. The Medical Care Act extended the opportunity for provinces to receive ongoing federal funding if they agreed to establish a government-controlled medical services agency that would ensure universal coverage at no cost for required medical care provided by a physician. The act also stipulated that citizens would continue to be covered when they were out-of-province temporarily. The last provincial medicare program was established by 1972.

In 1977, the federal government decided to not only abolish the conditions associated with obtaining federal funding support for health care, but also to eliminate the 50% contribution standard. From that point forward, federal funding support for health care was integrated into a broader social services. This new funding envelope was not conditionally based on how the provinces decided to spend the money meaning that the provinces could no longer rely on the federal government to contribute equally to the cost of rapidly increasing health care services.

While the provinces maintained their existing publicly funded medicare service offerings in the face of these changes (in addition to gradual introductions of other health care services as well), they began to introduce a series of patient user fees and some permitted certain extra billing by physicians and hospitals. This resulted in a public backlash and prompted the federal government to re-work its health care financing arrangements with the provinces once again.

In 1984, the federal government passed the Canada Health Act, which set out the conditions to which provinces were required to adhere in order to continue to receive federal funding support for health care. These conditions were based on the requirement that all medically necessary hospital and physician services to be covered include public administration, comprehensiveness, universality, portability, and accessibility. The legislation provided for financial penalties in the form of clawbacks of federal financing to be imposed on provinces that were found to be non-compliant with the conditions. However, while the threat of reduced federal funding did result in the fading of user fees and extra billing over time, the loose definition of what is a medically necessary service has resulted in some different interpretations of what is covered depending on the province.

While the mechanisms governing how the federal transfers are calculated and administered have continued to evolve since 1984, the Canada Health Act has been successful in ensuring that provinces have retained their respective universal coverage systems for hospital care and physician services.

Endnotes

Library of Parliament, “The Federal Role in Health and Health Care, September 20, 2013 – http://www.parl.gc.ca/Content/LOP/ResearchPublications/2011-91-e.htm.

Makarenko J, “Canadian Federalism and Public Health Care: The Evolution of Federal-Provincial Relations”, January 30, 2008 – http://mapleleafweb.com/features/canadian-federalism-and-public-health-care-evolution-federal-provincial-relations – division.

CHAPTER 2: The Canada Health Act and the Five Principles of Health Care

In Brief

In an effort to encourage the development of a consistent, national standard of health care in Canada, the federal government passed the Canada Health Act in 1984 which sets out the conditions that provinces must meet in order to qualify for federal funding support. Provinces that violate the act’s requirements are subject to reductions in funding.

For historical reasons, the national system covers only physician services and care delivered in hospitals. In the case of those services, provinces are all bound by five principles — public administration, comprehensiveness, universality, portability, and accessibility – plus a ban on extra charges if they are to qualify for the federal support.

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- Describe the Canada Health Act and outline its limitations

- Delineate the five principles of the basis of federal health funding support.

The Canada Health Act

The federal government passed The Canada Health Act (CHA) in 1984, in an effort to establish a common standard of health care for all Canadian citizens. In light of the fact that the federal government does not have constitutional responsibility for health care, it created legislation that links federal funding transfers to the provinces that agree to meet conditions set in said legislation, regarding the availability of health care for citizens.

So, while the federal government is unable to compel the provinces to provide specific health care services, the CHA outlines what standards must be met for provinces to be eligible for the Canada Health Transfer or CHT (funds provided annually by the federal government to help ensure a common level of health care service nationally).

The Canada Health Act (CHA) stipulates that in order to receive the CHT, insured provincial health care programs must meet a range of requirements, including five criteria (or national principles): public administration, comprehensiveness, universality, portability, and accessibility. Other conditions outlined are that provincial programs must also discourage user charges for direct services and extra billing for complementary offerings, and the provinces must report annually to the federal government and publicly recognize the federal contributions to their programs.

While the CHA covers the provision of insured services, for the purposes of the act, they are limited to those “medically necessary” services provided in doctor’s offices and hospitals. These include:

- Activities needed to prevent disease,

- Interventions involved in diagnosing or treating an injury, illness, disability, plus associated accommodation and meals

- Procedures intended to address a serious dental issue

- The services provided by physicians, other medical practitioners, and nursing services (i.e., physicians and their staff).

- Medications

- All medical and surgical equipment and supplies

Together, these services form the “medicare” system in Canada. It should be noted that the term “medically necessary” is not defined in the legislation and its scope is left to the provinces to determine.

Practically, this means that medicare services (i.e., hospital-based procedures and those offered in primary care facilities) are the only ones covered by the CHA. All other health services, including continuing care, home care and ambulatory care (including medications dispensed outside of hospitals) are considered “extended health services” which are not subject to the CHA, and which are provided by the provinces at their own discretion.

In reality, all provinces provide citizens with a broad range of health services that extend beyond medicare including nursing home and long-term care facilities, home care, palliative care, laboratory and diagnostic clinics, rehabilitation, assistive devices, eye care, dental surgery, and pharmaceuticals. The range of such additional health benefits, the rate of coverage, the categories of beneficiaries and the associated costs to patients vary greatly from one province to another.

The Five Principles of Health Care

In an effort to ensure that Canadians do not face financial or other obstacles to necessary health care services, the CHA requires provinces to uphold five principles. If they violate any of these principles (or the other requirements described above), they risk having portions of their CHT payments clawed back. The principles are as follows:

- Public Administration. The province must operate its health care insurance plan on a non-profit basis, and a public authority must administer the plan. While this provision’s intention is to ensure that provincial health insurance systems may not be operated by a private entity, the single-payer model adopted in Canada does not mean that the services offered by the system have to be provided by public organizations. In fact, the majority of publicly funded health services in Canada are delivered by private companies (most primary care practitioners are incorporated health care professionals and hospitals are typically community-based, not-for-profit corporations)

- Comprehensiveness. All “medically necessary” services provided by hospitals and medical practitioners must be insured. Given that the CHA does not specify the nature, range, or quantity of services that must be provided, the provinces have a great deal of discretion regarding what is considered medically necessary. In general, most health care services administered in a primary care facility, or connected directly to the facility are covered. The same is true for care administered in hospital or affiliated clinics. However, it is not unusual for additional charges to be imposed for a range of activities that a given province has determined should not be covered as part of the medicare system, and these are different from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

- Universality. All insured persons in the province or territory must be entitled to public health insurance coverage on uniform terms and conditions. While the terms and conditions may differ by jurisdiction, the fact remains that all residents within a jurisdiction can expect to be eligible for the same services.

- Portability. Coverage for insured services must be maintained when an insured person moves or travels within Canada or travels outside the country. For insured health services provided to eligible patients in another province, payment is made at rates negotiated by the governments of the two provinces. For services provided in foreign states, the expectation is that the provincial medicare system will reimburse the patient an amount that is at least equivalent to the amount the province would have paid for similar services rendered in that province.

- Accessibility. Reasonable access by insured persons to “medically necessary” hospital and physician services must be unimpeded by financial or other barriers, including such factors as income, age, and health status.

Provinces that fail to comply with the principles and conditions of the CHA are subject to financial penalties. In the case of patient charges, the federal government has the right withhold from the recipient province $1 for every dollar that an eligible beneficiary is charged for medically necessary services. Historically, several provinces have seen their payments docked for such violations, but such behaviour has quickly been addressed in future years.

For all other discrepancies, the amount of the penalty is discretionary, and subject to an elaborate dispute resolution mechanism that could involve third-party adjudication of the dispute. Ultimately the determination of whether a breach has occurred, the severity of that breach and the amount of the penalty is at the discretion of the federal minister of health. Thus far, there has never been a discretionary penalty imposed on any province, although there have been isolated cases of disputes for which acceptable settlements have been negotiated.

In general, the medicare system operates relatively smoothly. However, there are regular calls for extensions of the coverage to other areas of health care with critics often claiming that provinces are not living up to the principles enshrined in the CHA. Typically, the complaints revolve around patient charges for health services, but most often, the offending fees are related to services that are not captured under the medicare system. In some other cases, there are disputes related to the portability criterion or the requirement for public administration. In general, these are found wanting due to the fact that the provinces have a great deal of discretion in defining what services are medically necessary and, are perfectly within their rights to contract service delivery to private suppliers. The only time that becomes problematic is when the private clinics charge additional fees for services that would otherwise be provided free-of-charge within a public facility.

Endnotes

Madore O, “The Canada Health Act: Overview and Options”, Parliament of Canada, May16, 2005 – http://www.lop.parl.gc.ca/content/lop/researchpublications/944-e.htm.