MODULE 1. CANADIAN PHARMACEUTICAL SYSTEM OVERVIEW

CHAPTER 1: Introduction to Market Access in Canada

In Brief

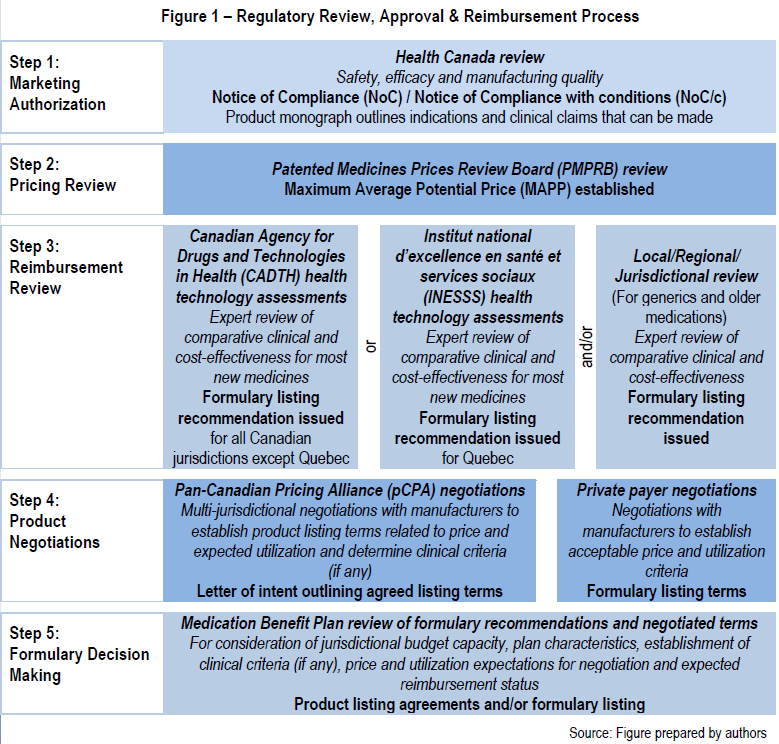

The market access environment in Canada has multiple stakeholders who each need to be understood thoroughly if a medication is to be launched successfully. Manufacturers need to navigate Health Canada’s approval process, a pricing review, a national health technology assessment (via the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health) and what seems like an endless number of public and private payer review bodies. The complexities of market access need to be well understood by those working directly with the approval bodies and payers, but it is also important that marketers and other members of the executive team have a clear understanding of the process in order to effectively plan strategy for their brands.

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter you will be able to:

- Provide an overview of the market access players in Canada

- Explain why market access success is critical to commercial success

- Identify who needs to have a thorough understanding of the market access

environment

Market Access in Canada

The Canadian pharmaceuticals market can be bewildering to those who are not familiar with how the regulatory and health services delivery systems work. Canada is a federation, consisting of a federal government, ten provinces and three territories. Under the Canadian constitution, the responsibility for health services delivery is provincial. However, the regulatory responsibility for such items as patents and the importing/exporting of goods and services rests with the federal government.

In addition, the federal government is the fifth-largest payer of pharmaceuticals in Canada as it has direct health care services responsibility for the Canadian Forces, First Nations and Inuit peoples, persons incarcerated in federal penitentiaries and veterans of the Canadian Forces and RCMP. As well, the federal government has a significant role in financing the health care systems of the provinces and territories.

In order to understand pharmaceutical marketing in Canada, it is important to have a fundamental understanding of how it operates and how it is evolving. Ultimately health care and subsequently, pharmaceutical care is driven simultaneously by federal, provincial and regional laws, regulations, guidelines and self-governance systems. These drivers, while restrictive in some cases, create a framework that allows for relatively accurate expectations on market potential, timing to revenue and resource requirements thereby reducing the risk in investing in Canadian pharmaceutical marketing considerably.

It is critical to recognize that in Canada there are no facets of the system that operate independently of one another. It is in understanding how all of the drivers in the system work together that the best business results can be obtained.

The process of regulatory review, approval and reimbursement is summarized in the five-step process in the Figure 1 below.

In order to operate effectively in Canada, it is critical to have a solid understanding of each of these five segments of the market. Failing to do so can expose the market entrant to undue delays, unexpected penalties and ultimately delays in revenues. A fundamental understanding of this system is likely to yield rewards as there is a willingness to adopt new products, provided they meet the standards set in the system.

The Critical First Step to Achieving Commercial Success

The Canadian regulatory and marketing approval process lags both the European Union and the United States making a well-planned market access strategy critical. With the patent life of a medication in Canada being finite, and the period of market exclusivity prior to patent expiration typically running between eight and ten years after market release, reducing the time-to-listing and avoiding any potential delays in reimbursement decisions will allow manufacturers to achieve maximum revenue potential over the life span of the medication.

A ‘reimbursement region’ is made up of government, opinion leaders and other stakeholders in the reimbursement infrastructure. One can see that reimbursement success will drive results for multiple traditional sales territories and, depending on the medication, can be worth tens of millions of dollars or more. Therefore, it can be said that future sales can be measured in terms of reimbursement, and in retrospect, reimbursement success will be measured in terms of sales. Conversely, lack of effective reimbursement often equates to drastically reduced business, revenue and profit if any at all.

Who Needs to Understand the Market Access Environment?

A successful submission strategy involves more than just government relations. It also needs to include stakeholder relations activities which will ensure strong advocacy for the new medication – these stakeholders include patient support groups, as well as prescribers, and other key opinion leaders in the therapeutic area. With this being said, it becomes clear that understanding the market access environment extends beyond the policy and reimbursement teams and should include marketing, sales and clinical teams within an organization.

Market access has evolved into a primary success factor for the pharmaceutical industry and in many cases it takes precedence over traditional sales and marketing. Successful market access demands new skills and approaches and is not just for policy experts and pharmaco-economists anymore. It has become a fundamental part of the sales and marketing strategy. In fact, it builds upon traditional sales and marketing training, including understanding the environment in which the business is operating (are payers experiencing financial belt tightening or loosening?); strong technical selling (strong clinical data remains important); relationship-building and maintaining, negotiating and delivering creative solutions based on the needs of the customer (in this case, the payer).

Market access training needs to build on the sales and marketing concepts above because sophisticated customers have sophisticated needs and these customers must be understood before they can be sold to.

If you do not know the system, it is very difficult to offer solutions and if you do not know the customer, it is very difficult to get them to decide in your favour. Credibility is critical to success.

CHAPTER 2: How Health Care is Organized in Canada

In Brief

There is no national health care system in Canada. Health care delivery, including medicare, which offers universal public coverage for care provided in hospitals and doctor’s offices, is a provincial (and territorial) responsibility in this country.

The federal government supports health in a number of ways. Specifically, it sets national medicare standards and moderates them through the Canada Health Act and a system of funding transfers. It also regulates health products, supports health research, undertakes health promotion and oversees national disease prevention and control. It also has a national health policy function and has responsibility for providing health care services to certain client groups.

Since provincial (and territorial) governments are primarily responsible for health care service delivery, they organize, run, and report on the operation of the system in their respective jurisdictions. As part of that system, they offer subsidized coverage for a number of health services, including medicare and others (e.g., prescription medications).

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter you will be able to:

- Understand how Canada’s health care system is organized

- Identify the key roles played by the federal government

- Identify the key roles played by the provincial governments

Overview

Many Canadians believe that there is a national health care system in Canada. That is a mis-conception driven by the fact that the same term – medicare – is commonly used to describe the public coverage offered to all Canadians. In fact health care in Canada is primarily offered via 13 separate provincial and territorial health insurance plans that follow a set of common standards regulated through federal funding transfers arrangements.

Over time, health care has become recognized constitutionally as an area primarily under provincial jurisdiction. This means that each province and territory operates its own separate health care system and delivers services to the public in the manner that its sees fit. Nationally, all provinces and territories individually have agreed to support the medicare model, which ensures that all Canadian citizens are able to receive hospital care and physician services without charges.

In an effort to standardize the medicare system nationally, the federal Canada Health Act was passed in 1984 as a means to establish the rules around what minimum standards provinces would have to meet with their public health care plans in order to qualify for federal funding support. Provinces that violate the act’s requirements are subject to reductions in funding.

The Canada Health Act

The federal government passed The Canada Health Act (CHA) in 1984. Since the federal government does not have constitutional responsibility for health care, it created legislation that links federal funding transfers to the provinces agreeing to its conditions regarding the availability of health care services for citizens.

So, while the federal government is unable to compel the provinces to provide specific health care services, the CHA outlines what standards must be met for provinces (and territories) to be eligible for the Canada Health Transfer or CHT (funds provided annually by the federal government to help ensure a common level of health care service nationally).

The act stipulates that in order to receive the CHT, insured provincial (and territorial) health care programs must meet a range of requirements, including five criteria (or national principles):

- Public administration

- Comprehensiveness

- Universality

- Portability

- Accessibility.

The provincial (and territorial) programs must also discourage user charges for direct services and extra billing for complementary offerings. The provinces (and territories) are also responsible for reporting annually to the federal government and must publicly recognize the federal contributions to their programs.

Covered services are limited to those deemed “medically necessary” that are provided in doctor’s offices and hospitals. Together, these services form the “medicare” system in Canada. All other health services are considered “extended health services” which are not subject to the CHA, and which are provided by the provinces and territories at their own discretion.

Federal Health Care Responsibilities

Despite the fact that responsibility for most health care services falls to the provinces and territories, the federal government still plays an important role in Canadian health care beyond its annual funding support to the provinces and territories to support the provision of health care services to their respective citizens.

First, as the national regulator of health products and hazardous materials, it is responsible for product review and classification, clinical trial oversight, manufacturing standards and quality control, and advertising of regulated products, among other related activities. A couple of ancillary activities to its product review and approval responsibilities are the regulation of patents related to medications and medical devices, and the associated regulation of the prices of patented medicines.

The federal government also contributes to national health by supporting health research initiatives, undertaking health promotion activities, developing and disseminating health information, and overseeing national disease prevention and control. It also has responsibility for emergency preparedness and disaster response. In addition, it supports various pilot projects in connection with provincial (and territorial) health care initiatives, undertakes a national health policy function that addresses key issues, and provides a national perspective on important health policy questions.

Finally, the federal government is responsible for meeting the health care needs of certain client groups for which it is directly responsible. In that context, several federal departments provide direct funding of health care services, for certain defined communities. These include:

- The Canadian Forces (Department of National Defense)

- First Nations and Inuit Peoples (Indigenous Services Canada)

- Prisoners incarcerated in federal penitentiaries and parolees (Correctional Services Canada)

- Veterans (Veterans Affairs)

- Refugees (Immigration Canada)

- Federal government employees, including RCMP members, parliamentarians and their political staff, and all eligible family members (plus Canadian Forces families)

The Territories

Canada has three territories that are not governed by provincial authority. The three regions – the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and the Yukon – remain under exclusive federal authority. However, in an effort to facilitate more local governance, the federal government has established a territorial administration in each via federal legislation that gives them delegated legislative authority and powers similar to provincial legislatures, including responsibility for public education, health and social services, and the administration of justice and municipal government.

As such, health services in the territories are provided to residents through their respective territorial health departments. These departments operate in very similar fashion to the way that provincial health systems do in Canada. In fact, they offer medicare services and a broad range of other health care services on the same basis as their provincial counterparts.

The only functional difference is that the territories are creatures of the federal government and governed by federal legislation, rather than operating as independent, autonomous and separate levels of government. However, since the federal government has granted the territories most of the same responsibilities as provinces, particularly as they relate to health care services, territorial residents experience the system in largely the same way as a provincial residents.

Provincial Health Care Responsibilities

According to Canada’s Constitution Act, provinces are responsible for “the establishment, maintenance, and management of hospitals, asylums and (charitable institutions) in and for the province, other than marine hospitals.” In addition, they have been assigned responsibility for specifically local and private matters, as well as property and civil rights (which allows them to regulate health professionals) and education (under which they provide health care training and education). Finally, these powers are “supplemented by the provinces’ general power over provincial public lands and assets, as well as provincial taxation power.”1 Together, they are the reason why health care has evolved as a provincial task.

Given that, each province (and territory) offers a broad range of publicly covered health care services. By the mid-20th century, most provinces offered at least some publicly funded health care services to residents, primarily in the form of hospital care, but also some coverage for physician care. With the advent of federal cost-sharing programs in the 1950s and 60s, each of the provinces responded to the financial incentive available and developed their own health insurance plans offering cost-free access to physician and hospital services to virtually all legal residents that collectively form Canadian medicare.

In addition, many health care services that are not covered by medicare are nevertheless offered as part of the provincial (and territorial) health care systems. These include subsidized coverage for home care, nursing supports and long-term care, cancer care, prescription medications administered in the community, care for injuries sustained in the workplace, public health services and a range of special programs for people with specific conditions and/or needs. When offered by the provinces (and territories), those additional services are subject to varying eligibility criteria, co-payments and coverage rules depending on the jurisdiction offering them.

Each province (and territory) has a ministry of health, which is responsible for setting health policy in the jurisdiction. While provincial (and territorial) health care delivery and governance differs slightly from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, each ministry of health is accountable to its respective government for organizing, running, and reporting on the operation of the system. Each ministry is responsible for relevant legislation and regulations, system design and governance, planning, resource allocation, standard setting, senior staffing and / or board / agency appointments and performance monitoring and reporting.

1 Leeson H, Constitutional Jurisdiction Over Health and Health Care Services in Canada, Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada, August 2002 -https://qspace.library.queensu.ca/bitstream/1974/6884/29/discussion_paper_12_e.pdf.

Health Care Services not Covered Publicly

The largest health spending categories that are generally not funded publicly in Canada are dental, and vision care services. Some emergency services are covered when administered in hospital, but virtually all routine dental and vision care is funded privately.

The same is true of non-prescription medications, of which only a tiny proportion is covered by public pharmacare, and only for very specific conditions.

Complementary or alternative health services, which encompass a wide range of non- medical health offerings, are exclusively privately funded. This includes traditional Chinese medicine, aboriginal healing rites, naturopathy, homeopathy, chiropractic care, therapeutic massage, reflexology, and many other alternative therapies that may be offered by regulated and non-regulated providers.

CHAPTER 3: Where Pharmaceuticals Fit in the Canadian Health Care System

In Brief

The funding model for pharmaceuticals in Canada is dependent upon where the prescription is written and dispensed. Hospitals are responsible for establishing a formulary and paying the cost of medications dispensed in that setting. They negotiate with manufacturers, either directly, or through group purchasing organizations. Whereas the availability of a medication in hospital is dependent upon their contracts with manufacturers, patients in the community are dependent upon their coverage through a federal or provincial government plan, their private health benefits provider, or their own ability-to-pay for the medications they require outside of hospitals.

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter you will be able to:

- Understand a hospital formulary and the importance to pharmaceutical manufacturers

- Discuss the differences between hospital and community pharmaceutical access

The vast majority of health care spending in Canada is done through the public purse. Almost all services provided within hospitals or physicians’ offices are covered by public funds under the terms of the Canada Health Act. Several other health services, such as home care, rehabilitation services and public health are also largely government-supported. However, many other health services, such as ophthalmology, dentistry and more, are typically offered as benefits provided by private health benefit providers.

Prescription medications are somewhat unique in terms of spending. Since pharmaceuticals are not included in the Canada Health Act’s basket of covered services, one might expect them to be primarily privately funded, but this is not the case. Due to a willingness on the part of the provinces and territories to deliver varying levels of medication coverage depending on the jurisdiction, about 40% of the annual national pharmaceuticals is publicly funded.2 This does not include medications dispensed in hospital, which would be funded publicly through the hospital budget.

2 Canadian Institute for Health Information’s (CIHI’s) annual National Health Expenditure Trends report.

After a new medicine receives marketing approval from Health Canada, the decision- making process shifts to the payer environment to determine how it would be funded. The following sections distinguish how the particular setting in which a medicine is administered determines how funding decisions are made.

In Hospitals

Under the terms of the Canada Health Act, all medications administered to patients in hospitals are fully funded by the public health care system for all Canadians. That means that funding decisions are left to the institutions to determine.

In general, decisions about which new medicines should be added to the institution’s formulary are the responsibility of a given hospital or health authority’s internal pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committee. The P&T committees are typically made up of health professionals and other experts who are affiliated with the institution(s) in question.

In some cases, provincial/territorial medication review bodies get involved and this trend is becoming more common as public payers increasingly are looking to synchronize hospital purchases with provincial/territorial formularies in order to achieve continuity in the types of medications delivered between the two care modes.

Pharmaceutical procurement in Canadian hospitals and institutions is a complex process. And it is getting even more complex as government involvement, collaborative/group purchasing, single-supply chain management outside of pharmacy and the role of technology in hospital services evolve. Additionally, as hospital groups begin to merge into bigger regions or local networks, discussions about centralized production and formulary initiatives are taking place. The supply chain represents a large percentage of total expenditure for health care providers and, as such, it provides a logical opportunity to look for efficiencies.

Implications for Pharmaceutical Manufacturers

In many cases, the hospital sector represents a relatively minor component of a given medicine’s potential market in Canada. Therefore, with the exception of medications that need to be administered in a supervised clinical setting, the pharmaceutical industry’s main market access efforts are directed at the community setting.

Still, the industry does focus some of its access energy on hospitals as required to optimize uptake of their treatments. In some cases, hospital formularies represent the only market for a given product in recognition of the complexity of the products and/or the need for supervised administration. And that proportion is increasing as the number of specialty medications grows.

Given these trends and the tendency for patients to be stabilized on certain medications while in hospital, many in the industry have begun to re-examine the importance of hospital formularies, not only for highly specialized medications, but also for more traditional ones, where the added exposure, particularly among specialists (who are often thought leaders in the physician community) affiliated with the hospital can benefit a product significantly.

In the Community

Although any medication in receipt of a Notice of Compliance from Health Canada can be marketed and sold in the community, a positive formulary listing is often the difference between market failure and success.

Patients often prefer to be prescribed a medication that is listed on a public medication plan or their private health benefit provider formulary rather than a treatment option that is not in order to avoid having to pay out-of-pocket for the prescription. That is because when medications are prescribed that are not listed by a patent’s public or private plan, they become the responsibility of the patient to reimburse.

Clearly then, the capacity of a manufacturer to obtain a third-party formulary listing is a key factor in the success of a community-based product. That factor, along with an effective marketing strategy that clearly differentiates the product, also plays a significant role in how a medicine will be prescribed in the community.